The hip joint is an extremely stable ball-and-socket joint. The rounded head at the top of the thigh-bone (femur) links with a shallow cup-shaped hollow called the acetabulum, which is part of the hip-bone (innominate bone).

The two hip-bones form the sides of the pelvic basin: you can feel the bony ridge which forms the upper edge of each hip-bone on either side of your body just below waist level, and the bony prominence of the pubis is formed where the two hip-bones meet in front. You can’t touch the hip joint itself, as it’s located quite deeply, and is well surrounded by a padding of muscles and tendons.

To the side of the hip, the top of the thigh-bone forms a bony prominence called the greater trochanter, which you can feel with your fingers. The neck of the thigh-bone connects the bone’s head to its shaft. It is angled upwards and inwards, and is about 2 inches / 5 centimetres long. The head and neck of the thigh-bone are specially constructed to withstand and transmit pressure through an intricate kind of latticework, called trabeculae, within the bone structure.

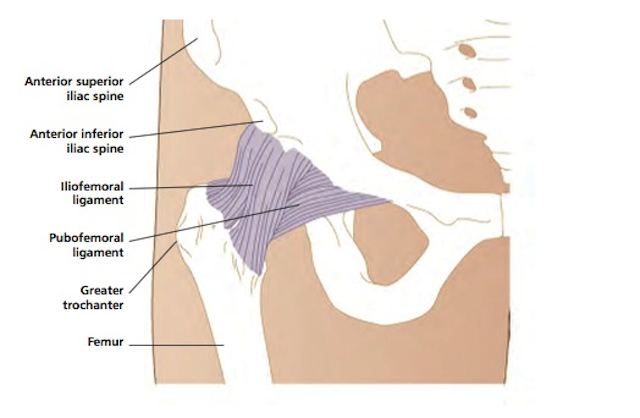

The bones of the hip joint are tightly enclosed in a fluid-lined fibrous capsule, thickened at the front into one of the strongest ligaments in the body, the iliofemoral ligament. There are other ligaments around the joint, and a much weaker one in the centre (which many people don’t even have) joining the head of the thigh-bone to the acetabulum.

The blood supply to the head of the femur is relatively limited, whereas the neck of the bone has a richer supply. The nerve supply is mainly from the femoral and obturator nerves, including nerves from branches which supply some of the muscles around the joint.

Functions

The hip is very stable. It allows for a wide variety of movements, such as twisting and turning as we walk or run, breast-stroke swimming, dancing, sitting cross-legged or in lotus position, hopping and bounding in different directions. Doing the splits forwards or sideways depends on extreme mobility in the hips and lower back. The ability to spread the legs wide apart is important for childbirth: if the mother has abnormally stiff hips, Caesarian section may be necessary for a safe delivery.

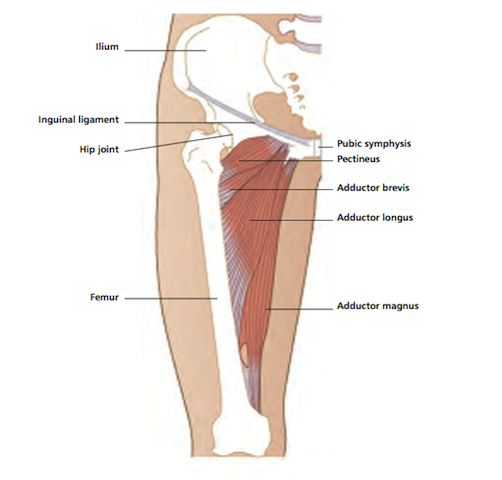

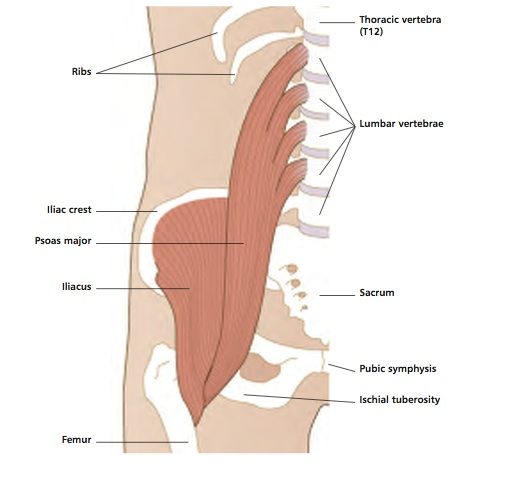

The hip can bend to bring the leg forwards into flexion, mainly through the action of the hip flexor muscles; it extends to take the leg backwards, mainly through the gluteals and hamstrings; it abducts taking the leg outwards away from the other leg (hip abductors); it adducts to bring the leg in (hip adductors); and rotates inwards, or medially, and outwards, or laterally (combinations of muscles do these movements).

Flexion and outward rotation have the greatest freedom of movement, whereas extension is limited to about 10-15˚. The hip is the link between the leg and the pelvis. It therefore influences, and is influenced by movements, postural patterns and abnormalities anywhere in the leg or trunk. It compensates for weakness or imbalance on either leg and each side of the body.

Vulnerability

Major force is needed to disrupt the structure of the hip. Fracture to the bones round the hip happens more easily than a dislocation of the joint. Such injuries can and do happen, but the vast majority of hip problems are due to attritional damage.

Even in the absence of injuries or accidents, the hip is subjected to enormous pressures in the course of a lifetime. When we stand or walk, the hip transmits the weight of the trunk to the legs, under the additional pressure of gravity. When we are sitting down, the hips bear the weight of the trunk, head and arms, plus gravity, against the opposing force of the surface we sit on. When we run, jump or hop, the pressure on the hip joints increases dramatically, softened only by the efficiency with which our muscles can absorb the shock.

Imbalance

It’s all too easy to damage the hips in our everyday life, without realizing it. Our hips act independently of each other, but they are also a pair, and they need to be kept in balance, in terms of movement, stability and muscle activity.

Careless posture can create overload on the head of the thigh-bone, leading to micro-damage in the bone cartilage, the wear-and-tear degeneration commonly known as “arthritis”. Examples of potentially damaging postures include standing with your weight balanced over one leg, sitting on a chair with your legs crossed at the thighs or ankles, sitting with with one or both legs tucked under you, or sitting or standing with one foot raised on a step or support. Poor postural habits very often arise because of being still for long periods. All too often, sitting or standing in a bad position seems comfortable or natural, making it harder to want to correct it.

Many sports and physical activities contribute to imbalance between the hips, including javelin throwing, triple jumping, hurdling and fencing. Track running puts abnormal pressure on the left hip, because the athlete has to lean into the bends. Excessive running, especially long distance training, can lead to overload on the hips, not only because of repetitive impact, but because hip flexor muscles on the front of the joint shorten, and the adductor muscles along the inner thigh work harder to compensate when the front-thigh muscles get tired. As the hips flex and turn inwards, there is abnormal pounding pressure on a small part of the head of the thigh-bone. In children as well as adults, running with the hips turning inwards is a sure sign that they are trying to do too much relative to the strength and endurance of their muscles.

It’s worth noting that most often a severely arthritic hip becomes fixed in the flexed and internally rotated position. Sometimes the arthritic hip turns outwards abnormally. Limitation of movement in any direction or position can be harmful to hip health.

Classical ballet dancers are trained from an early age to turn their feet outwards through splaying their hips into outward (lateral) rotation. This position alters the joint’s normal weightbearing pattern and can contribute to arthritic wear-and-tear. Turning the hips outwards also affects the feet, and is a cause of dancers’ bunions.

Injuries in many parts of the body can have a knock-on effect on one or both hips.Back problems almost invariably affect one or both hips, and sometimes a problem around the hip causes symptoms just like those which might be caused by a back problem.

If you limp due to a leg injury, the leg’s normal shock-absorbing mechanisms are disrupted, which leads to abnormal load on both hips as you walk. If one leg is immobilized and you can’t take your weight through it at all, all your bodyweight goes through the other leg if you hop around, and most of the load is concentrated at the hip. Crutches help to reduce the load. When you are upright, the immobilized leg is bent, which shortens the muscles and tendons over the front of the hip and at the back of the knee.

Achilles tendon problems can affect the hips, by altering normal walking patterns. Sometimes Achilles tendon pain is not localized but referred from further up the leg or the lower back, and a stiff hip can play a part in this.

Arm, especially shoulder problems can also affect the hips. This is because the normal swing of the arms during walking is disrupted. The shoulder tends to drop if you are guarding your arm, or if it is in a sling when you walk. This causes more loading on the hip on that side, besides leading to some shortening or tightening in the latissimus dorsi muscle, the large complex muscle which extends all the way from the top of the hip bone, just below the waist, to the front of your shoulder.

How to protect your hips

* Keep your hips mobile, paying special attention to the full twisting (rotation) movements

* Keep the muscles and tendons around the hips strong and flexible

* Avoid sitting on low, soft seating

* Don’t sit still for long periods:

- exercise your stomach muscles, pelvis and feet as often as possible

- get up and move around as often as you can

* Try to keep your legs in symmetrical alignment most of the time

* Don’t cross your legs while sitting or lying

* Don’t curl your legs under you while sitting

* Don’t stand with your weight shifted over one leg

* Try to do balanced physical fitness activities, mixing weightbearing (eg walking, running) with non-weightbearing (eg swimming, cycling, gym equipment training)