The knee is complex: it's not a simple hinge joint.

It is vulnerable to injuries and painful conditions in males and females of all ages, in all situations. It is the most commonly injured joint in sport. In the young, knee pain and certain types of injuries can occur in association with growth phases. In older age the joint can deteriorate as the result of poor postural habits, excessive weightbearing activities, previous injuries or pain conditions, inappropriate diet, circulatory problems, hormonal influences and hereditary factors.

Structure

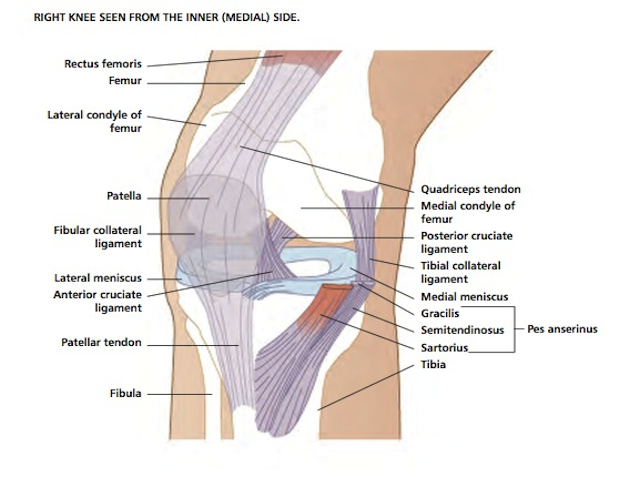

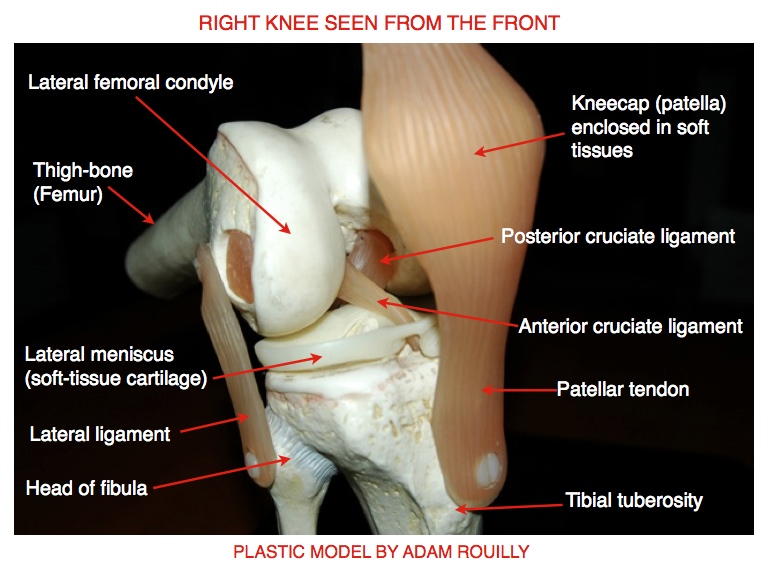

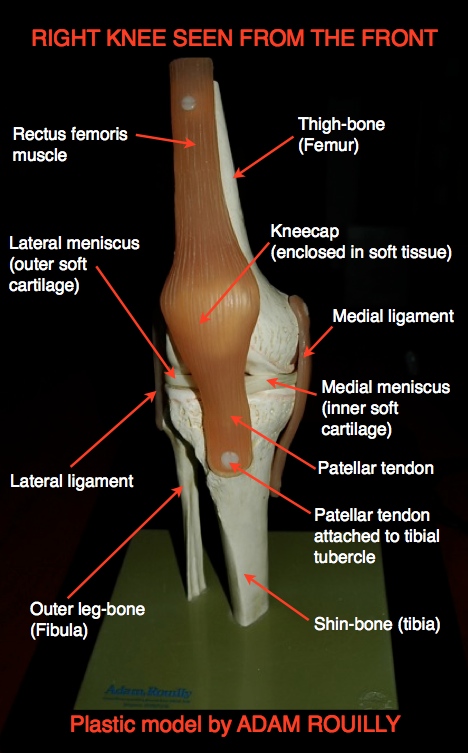

The knee joint consists of three parts. There is the main knee joint, formed between the lower end of the thigh-bone and the top of the shin-bone. The knee-cap is a free triangular piece of bone over the front of the knee, forming the patellofemoral joint. The knee-cap is loosely held within the lower end of the quadriceps muscle group, which is attached by the patellar tendon from the tip of the knee-cap to a prominent bump at the top of the shin-bone called the tibial tubercle. The third structure in the knee joint complex is the tibiofibular joint, which is formed between the top ends of the shin-bone (tibia) and outer leg-bone (fibula).

The knee is bound together by ligaments and a fibrous capsule. In the centre of the main knee joint are the two strong cruciate ligaments which bind the thigh-bone to the shin-bone. The anterior cruciate is the longer and weaker of the two. It is attached behind the posterior cruciate on the thigh-bone, and comes forward at an angle to be attached in front of the posterior cruciate on the top of the shin-bone. The posterior cruciate ligament is shorter and more vertical than the anterior. The sides of the knee are protected by the collateral ligaments: the medial ligament protects the knee on its inner side (facing the other leg), and connects the side of the thigh-bone to the shin-bone. The lateral ligament lies on the outer side of the joint and connects the side of the thigh-bone to the top of the outer leg-bone (fibula). The back of the knee is also protected by ligaments, but these are weaker than the others. There is no ligament as such on the front of the knee, only the patellar tendon which connects the tip of the knee-cap to the tibial tubercle. The patellar tendon is sometimes called the patellar ligament, but it is functionally a tendon.

The knee’s capsule encloses the back and sides of the knee, but doesn’t cover the front or the knee-cap. The knee is lubricated by its fluid-forming synovial membrane, which lines the capsule and extends around and within the knee, and about 5 cm above the knee-cap. Numerous bursae, little fluid-filled sacs or pouches, lie between the various soft structures around the knee, to ensure friction-free movement.

The knee’s soft cartilages (menisci) are crescent-shaped, rubbery-looking structures attached to the top of the shin-bone. The cartilage on the inner side, the medial meniscus, is the larger of the two, and is attached to the medial ligament. The lateral meniscus is more rounded in shape, and is not bound to any of the main ligaments. The menisci are lubricated by the synovial fluid in the main knee joint.

Functions

The main muscles which act on the knee are the quadriceps group over the front of the joint and the hamstrings at the back, helped by other muscles which co-ordinate with them. The quadriceps group straightens the knee against gravity, and controls bending movements done under the influence of gravity, for instance when we walk down stairs or squat down slowly with control. The hamstrings bend the knee against gravity, and control the reverse movement. The two groups of muscles interact and harmonize, shortening and paying out by turns, in most activities involving our knees. The soft cartilages (menisci) act as shock-absorbing buffers, softening impact against the bones forming the knee.

Because the knee is a condylar joint rather than a simple hinge, it automatically twists slightly as it straightens and bends. We can twist the knee consciously by turning the foot inwards and outwards while sitting with the knee bent to 90 degrees. Muscles at the sides of the knee perform these actions.

The knee has enough freedom of movement to allow us to do a wide variety of actions, such as kneeling, squatting, running, jumping, kicking, skiing and dancing. We can change direction nimbly largely because of the special combination of freedom and stability in our knees.

Vulnerability

Although the knee is quite a strong and stable structure, its mobility makes it vulnerable to injury through shearing, twisting and jarring stresses.

Any part of the knee complex can be injured. Probably the most common problem is pain related to the knee-cap joint, which is called by various names, including kneecap pain syndrome , anterior knee pain, patellofemoral pain syndrome, retropatellar pain and “runner’s knee”. Cartilage, cruciate ligament and medial ligament injuries are familiar to most people because famous footballers suffer from them. They can happen to anyone, through different causes. Young people can suffer from pains related to growth phases in the knee bones: Osgood-Schlatter’s condition (inflammation of the tibial tubercle) is a common problem for 12-14-year-olds. In older people wear-and-tear degeneration (osteoarthritis, osteoarthrosis) happens, with or without pain.

Signs and symptoms

Knee symptoms such as pain and swelling can happen through different causes, and can be misleading. There are few pain nerves inside the centre of the knee, so a serious injury to a deeply placed structure like one of the cruciate ligaments can be surprisingly painless, whereas a relatively trivial injury close to the surface can cause severe pain. Referred pain from the hip or lower back can mimic knee pain, or complicate a knee problem. Swelling can be a symptom of injury, inflammation or occasionally disease. Self-diagnosis is not recommended. Assessment and diagnosis are best done by competent practitioners.

Vastus medialis obliquus: "the key to the knee"

The key to functional recovery from any knee problem is the function of the vastus medialis obliquus muscle (VMO), which controls the knee from its inner side. The vastus medialis muscle is part of the quadriceps muscle group, and runs down the front inner side of the thigh, and at its lower end has more or less horizontal fibres which are attached to the inner side of the knee-cap. These horizontal fibres (the VMO) act to draw the knee-cap over towards the inner side of the thigh, and to lock the knee when it is straightened fully.

Whenever the knee is painful, the VMO is inhibited almost immediately, so that the knee can no longer be straightened actively. This is at least in part a protective reflex. The knee is held slightly bent. In a four-legged animal, it would be held off the ground. We two-legged humans have the option of hopping, walking using one leg and crutches, or limping.

Getting the VMO to function again is not easy, as the other bigger parts of the quadriceps group take over and make it difficult for commands through the nerve signals to reach this small muscle. It is therefore an uphill task to re-train the VMO’s nerve-muscle co-ordination through exercises alone. In my experience, the most efficient way to restore VMO function is to use neuromuscular electrical stimulation. This may be applied by a practitioner, and it can be done as a self-help active treatment/exercise method (depending on your practitioner’s approval).

Regaining full control of the VMO is vital for the stability of the knee. Exercises which integrate the VMO so that it works in harmony with the knee’s other controlling muscles are part of the stabilizing process, and these are set out in my primary leg exercise programme. The primary exercises are done as quickly as possible after an injury or the onset of pain, as soon as the specialist or practitioner allows, and they should be continued throughout the whole recovery period. In the second phase of recovery, more demanding exercises are introduced (the intermediate leg exercise programme), which are geared to returning to normal life. For sports players there is a third phase of exercises related to sports activities - the sport-related rehabilitation exercises.

To me, defining points in knee recovery are the patient’s ability to straighten and relax the knee with full control of the VMO, and the ability to squat down without pain or limitation. The full squat is only attempted when the knee is fully stable and has regained mobility. There are of course some situations where these goals cannot be reached, and then one works to get as close to them as possible.

Rehabilitation and recovery

To get maximum benefit from any rehabilitation exercise programme, you need to do it consistently for at least six and preferably twelve weeks. Even for a minor knee problem, I recommend six weeks for recovery before the patient returns to any kind of knee-stressing activities. Yes I know the tales of footballers getting back on the pitch two weeks after cartilage surgery and the like. But have you looked at the less attractive after-effects, including re-injury, secondary related injuries in other parts of the legs or even up to the back, and, worst of all, crippling arthritis early in middle age? Full recovery from a knee problem does not happen to a set time-scale. People respond individually to injuries, pain and rehabilitation. Every patient has to be allowed whatever time is needed to regain the knee function they need for their normal activities.

Note: Adam Rouilly are international manufacturers and suppliers of anatomical models, charts, and training simulators for healthcare professionals