Bones and joints

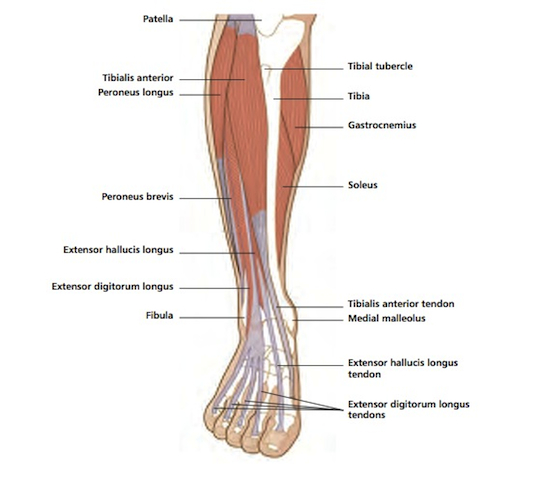

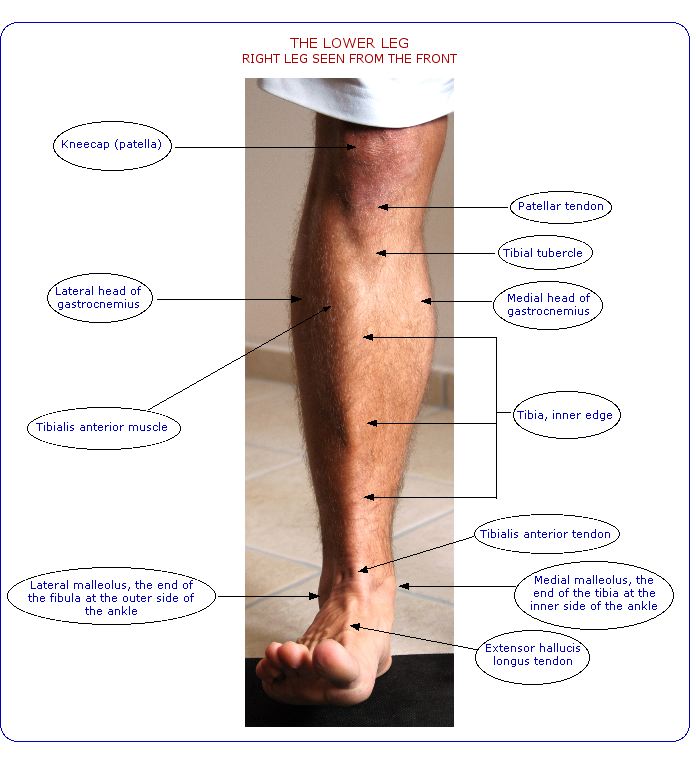

The shin-bone (tibia) is the main weightbearing bone which connects the knee to the ankle. You can feel the front edge of the bone along the inner side of the lower leg, where it lies directly under the skin. At its lower end, the shin-bone has a small protrusion, the medial malleolus, which forms the inner edge of the ankle, and which you can feel with your hand.

On the outer side of the lower leg is the outer leg-bone (fibula), a light non-weightbearing bone which lies at the outer side of the knee and ankle. It expands into a knob (lateral malleolus) at its lower end to form the outer side of the ankle. With your hand, you can feel the head of the fibula at the side of the knee, and you can feel the lower end down to the ankle. In between, it’s more difficult to feel as it’s covered over by the calf muscles.

The tibia and fibula are connected at the top and bottom by strong ligaments to form the superior (upper) and inferior (lower) tibiofibular joints. The upper joint is synovial, as it is bound within a fluid-filled capsule, whereas at the lower joint the bones are bound together only by ligaments in what is technically known as a syndesmosis.

There is a very slight gliding movement between the two bones at their upper ends, which happens automatically when the knee moves, and to an even lesser extent during ankle movements. At its lower end, the fibula twists slightly outwards when the foot is drawn up at the ankle into dorsiflexion, so the gap between the tibia and fibula is slightly enlarged. This happens to allow space for the bone to glide into, as the front part of the ankle’s talus bone is wider than the rear.

In between the two bones, almost down their whole length, is a strong band called the interosseous membrane, which creates a partition between the front and the back of the lower leg. Muscles which move the foot and toes follow the line of the bones. At the upper end of the tibia and fibula there are attachment points for tendons from thigh muscles which act on the knee.

Muscles and movements

At the front of the lower leg, the anterior tibial muscles lift the foot and toes upwards against gravity. Tibialis anterior brings the top of the foot up at the ankle, and turns the foot inwards and slightly upwards into inversion. Standing up, it helps keep the leg in position over the ankle, and stabilizes the medial longitudinal arch of the foot, especially in the push-off phase of walking or running. Tibialis anterior forms the fleshy bulk on the outer side of the tibia.

The outer toes are drawn up by the extensor digitorum muscle, the big toe by extensor hallucis. These extensor muscles end in the cord-like tendons which you can see and touch on the top of the foot leading down to the toes.

The peroneus longus and brevis muscles lie along the outer side of the lower leg, and turn the foot outwards, into eversion, when they work against gravity. They also help to point the foot downwards, and peroneus longus is a support for the foot’s arches. The peronei support the foot’s arch on tiptoeing or pushing off to run.

Behind the tibia and fibula, under the calf muscles, are deep-lying muscles which point the foot and toes downwards against gravity. Flexor hallucis longus points the big toe downwards, and flexor digitorum longus flexes or curls the rest of the toes. All these flexor muscles are especially active when you stand or walk on tiptoe. Tibialis posterior turns the foot inwards, into inversion, and also acts with the more superficial calf muscles to point the foot downwards at the ankle. During walking, tibialis posterior helps control the foot, preventing it from folding too far over inwards into pronation.

The patellar tendon, the end-point of the quadriceps muscle group, is attached to the tibial tubercle, a knob of bone near the top of the front of the shin-bone. The quadriceps group straightens the knee against gravity. The hamstring tendons, which bend the knee against gravity, are attached to the back of the upper ends of the tibia and fibula. Popliteus is a small, flat, significant muscle at the back of the knee, linking the knee capsule to the back of the upper end of the tibia. It starts the movement of bending the knee from the fully straightened position. It also twists the tibia inwards (in medial rotation) in relation to the femur (thigh-bone), and helps to keep the femur in the right place during crouching or squatting.

Vulnerability

Because it lies so close to the surface, with no protective soft-tissue covering, the front edge of the tibia is especially vulnerable to damage from direct contact, such as a bump against the edge of furniture, a kick in soccer, or a hit with a hockey stick. Bone bruising can cause a swollen lump to form on the surface of the bone, technically called a subperiosteal haematoma.

Severe trauma can cause fractures in either or both shin bones, especially in high-risk sports such as downhill skiing. Either bone can also be cracked or broken in conjunction with a bad ankle sprain. In young children, trauma can cause greenstick fractures or damage to the epiphyses (growth areas in the bones).

A fracture, a severe blow or prolonged pressure at the upper end of the fibula just below the knee can damage the nerve which winds round the neck of the bone at this level. This can cause tingling or numbness in the pathway of the nerve down the lower leg. If bad enough, part of the leg goes “dead”, or the muscles which lift the foot at the ankle stop working, causing a “dropped foot”.

Stress fractures in the tibia or fibula are relatively common injuries among runners, usually caused by doing too much repetitive training. Stress fractures can happen in any part of the bones, at any age. So-called 'shin splints' are often stress fractures rather than muscle problems. In teenagers, the tibial tubercle at the top of the shin-bone is especially prone to damage through excessive repetitive stress. This injury is known as Osgood-Schlatter’s condition, and is technically an apophysitis.

Any of the muscles and their tendons in the lower leg can be injured through trauma or overuse. The soft tissues may be strained or torn in varying degrees. In some cases, overuse injury to the soft tissues causes swelling within the enclosing muscle sheath: this is known as compartment syndrome. It can cause quite severe pain during exercise, as the excess fluid gathers and becomes trapped within the sheath. This injury is called anterior tibial compartment syndrome when it affects the muscles at the front of the shin, and posterior tibial compartment syndrome if it happens behind the tibia.

Protecting the shin

It’s essential to wear shin guards for contact sports like soccer and field or ice hockey. Shoes and boots should be chosen with care: they must fit properly, and be suitable for the purpose, be it sport, walking or a sedentary daily life.

Look after your circulation at all times: never sit with your legs crossed; don’t wear tight socks or shoes; don’t wear knee-high boots all day; avoid sitting still for long periods; walk about, activate your trunk muscles, move your arms and legs, exercise your hands and feet as often as possible if you have to sit or stand for long periods; do deep breathing exercises at intervals; and try to take some regular exercise every week.

To avoid overuse injuries, you have to limit the amount of repetitive activities you do, especially if you are a runner. Do alternative training such as gym workouts, yoga, pilates, tai chi or martial arts for overall body condition and body balance. Always include rest days within an intensive training programme.

Never do activities which cause or aggravate leg pain. Avoid repetitive training such as running if your calf or shin muscles are tight from cramp or previous hard training sessions.

© Vivian Grisogono 2008, updated 2016